Tennis Elbow

What is it?

Almost every athlete at one point or another in his or her career will suffer from tendonitis of the elbow, or tennis elbow. Tendonitis is a diagnosis which is often made but less often understood. To fully comprehend what the term means, you must first break down the word tendonitis into its two word basic parts.

The first part, of course, is tendon. This is the strong band of tissue, which is at the end of the muscle that serves to anchor the muscle onto bone.

When the muscle contracts it pulls on the end of the strong band of tissue, which is the tendon. This in turn pulls on the bone and provides movement across the joint. For all intents and purposes, a tendon is really part of the muscle itself, but is devoid of the muscular fibers and allows the muscle to attain a greater length across the joint.

The second part is “itis.” This is term simply means inflammation. It does not, as is commonly misunderstood, mean infection. The use of the term can change with the piece of anatomy. When it is a tendon, it is tendonitis, but it can also refer to the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritonitis) or the thin lining of the brain or spinal cord (meningitis).

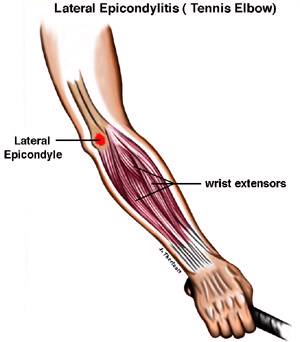

Some areas of the body are much more prone to tendonitis than others, in particular the elbow and shoulder. Probably the most commonly known form of tendonitis is tennis elbow (also called lateral epicondylitis). Tennis elbow develops where the muscles on the back of the forearm join together to form one tendon (the lateral epicondyle) in the elbow. When this tendon becomes inflamed from repetitive motion and over-use, tendonitis, or tennis elbow, occurs. These strong muscles on the back of the forearm serve to cock the wrist up and back which is, of course, the starting position for the tennis stroke. If this is done repetitively it can cause tendonitis at the elbow. Although the common term for this condition is “tennis” elbow, it can of course be obtained in any sport requiring repetitive motion of these muscles. For that matter, it can also be work related with manual tasks in the work place.

Some areas of the body are much more prone to tendonitis than others, in particular the elbow and shoulder. Probably the most commonly known form of tendonitis is tennis elbow (also called lateral epicondylitis). Tennis elbow develops where the muscles on the back of the forearm join together to form one tendon (the lateral epicondyle) in the elbow. When this tendon becomes inflamed from repetitive motion and over-use, tendonitis, or tennis elbow, occurs. These strong muscles on the back of the forearm serve to cock the wrist up and back which is, of course, the starting position for the tennis stroke. If this is done repetitively it can cause tendonitis at the elbow. Although the common term for this condition is “tennis” elbow, it can of course be obtained in any sport requiring repetitive motion of these muscles. For that matter, it can also be work related with manual tasks in the work place.

The actual pathology of the underlying cause of tendonitis is still subject to debate. Some researchers feel that it is a true inflammation of the tendon itself while others feel that it is micro hemorrhages (bleeding) into the fine tissues of the ligament. Still, other researchers have postulated that it is not the tendon at all but rather an inflammation of the periosteum (outer lining of bone) and is therefore more truly called a periostitis. These arguments are academic in nature because the symptoms to the athlete remain the same: pain.

There are many factors that together contribute to tendonitis. Probably the most common is repetitive overuse of the joint, which frequently occurs in racquet sports with the repetitive stroking of the ball with the wrist in a cocked position. In tennis itself, it has often been thought that it originates from improper stroke technique. This is particularly true in the backhand. Researchers have broken down the two most common faults into 2 categories. Unfortunately, most of us probably fall into the larger group, which represents the category of players who are casual athletes. For these players, the most common problem is overuse syndrome resulting from the the overhand serve. The repetitive hyper-pronation of the wrist causes recurrent stress on the lateral epicondyle of the elbow. Other common problems are the use of an incorrect grip size on the racquet, or a racquet that is the wrong weight for the player.

Signs and Symptoms

The symptom patients most often complain of is a diffuse ache around the elbow joint which is usually able to be tracked down to one small local area that is tender on touch. It is particularly worse with active use and usually the athlete will complain about stiffness and a sensation of swelling after playing. Interestingly, if tendonitis occurs on the inside of the elbow rather than the outside, this is known as “Golfers’ Elbow.” Golfers’ Elbow, or medial epicondylitis, is less common than tennis elbow but just as painful.

Treatment

The treatment of chronic tendonitis most often begins with simple rest from the activity that caused the problem. Most athletes are not comfortable with this as the only treatment, and therefore use splints worn around the forearm to limit forearm muscle contraction. Other forms of non-aggressive treatment consist of physiotherapy, with modalities such as ultrasound and icing the affected area. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Aspirin, Motrin, and Naprosyn can also be added to the treatment regiment.

Surgical intervention is also option, but this should be a last resort after all other treatments have failed. Before surgery is contemplated, the area is usually injected with cortisone if the patient has been refractory to all other treatment. However, cortisone should not be given repetitively into the same area, as it can cause permanent damage to the tendon if done too often. When done properly, cortisone injections are a very effective treatment and can often remove the need for surgery. If the patient remains symptomatic or has only a brief period of relief with the injection, surgical options should then be explored. Surgery usually consists of a release of the common extensor of these muscles from the lateral epicondyle, and removal of the scar tissue in the area. This surgery can be performed outpatient, and the results are usually excellent.

The risks include infection, damage to nerves and blood vessels, stiffness, recurrence of symptoms, anesthetic problems, etc. Make sure you understand the risks prior to having surgery. Although surgery is often able to provide relief, it would be better if tennis elbow could be avoided all-together. This consists of a reasonable approach to the sport, using proper stroke technique. It is not advisable to pick up a racquet and try to learn how to play tennis, or any other racquet sport, by playing every day after never having played the sport before. If you do pick up the sport so rapidly, this will almost guarantee overuse and tendonitis. Switching to a two-handed backhand will also usually help relieve most problems. Obviously, this is not possible in squash or racquetball.

The best approach to tendonitis is to avoid it in the first place with proper care and form. If it does occur, however, the best thing to do is to treat it as soon as possible. Once it becomes chronic, tendonitis can be very difficult to cure. Athletes should seek the advice of a qualified medical doctor who can best advise them and prescribe the appropriate therapy or medication.